Labor’s 2024 tax reforms have failed low-paid workers

Can the Labor Party save itself from an electoral backlash in 2025 by accepting that its 2024 tax reforms have failed low-paid workers and their families?

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

Labor’s 2024 tax reforms have failed low-paid workers

Can the Labor Party save itself from an electoral backlash in 2025 by accepting that its 2024 tax reforms have failed low-paid workers and their families?

And will it do something about it?

Brian Lawrence

In explanation of the Albanese Labor Government’ announcement in January 2024 that it would modify the legislation providing for “Stage 3 tax cuts”, the Federal Treasurer, Dr Jim Chalmers, made the following statements in his press conference:

• “This is a situation where every Australian taxpayer will still get a tax cut but there'll now be a bigger emphasis on middle Australia.”

• “We are returning bracket creep where it matters most and where it hurts the most, which is in middle Australia”.

They were promises that the Government kept, much to the disadvantage of low-paid working Australians.

The Albanese Government promoted the tax cuts that it delivered from 1 July 2024 as a boon to the living standards of low- and middle-income Australians, while emphasising its decision to reduce the tax cuts for higher income earners that had been enacted in 2019 by the Morrison Government.

At the same time, it was tone deaf to the position of low-income earners who have suffered from low wage increases, compounded by increasing average tax rates, or tax bites, in the years since the Rudd-Gillard-Rudd Labor Governments of 2007 to 2013.

On 15 February 2024, only 21 days after the Government’s announcement, the legislation passed the House of Representatives and 12 days later, on 27 February 2024, it passed the Senate. Has there ever been taxation legislation such as this, framed with a 10-year horizon, passed in a shorter time?

The selling and enacting of the tax changes was a rushed job, designed to enhance Labor’s chances in the Dunkley by-election on 2 March 2024. Questioning and dissent among the parliamentary backbench and within the Labor heartland did not emerge.

The Coalition’s Plans to re-balance the tax system

The objective underpinning the Morrison Government’s 2019 three-stage tax legislation was the rebalancing of the relative tax burdens across the income groups. Its strategy was to combine short-term tax cuts for low and lower-middle income taxpayers with long-term tax cuts for high-income taxpayers.

The Morrison Government’s tax policy was clearly contrary to the interests of the Labor base and when Labor had the opportunity to respond to that policy after its re-election in May 2022, its response was uncertain, delayed, and then insufficient.

It is clear that, despite the Labor Government’s rhetoric, its 2024 tax package modifying the Morrison Government’s Stage 3 changes, has failed low-income taxpayers and has treated them less favourably than middle- and high-income taxpayers. The Morrison Government’s strategy to make substantial changes to the progressive tax system was mostly locked into place by the Labor Government in 2024.

The figures discussed in the following sections are taken from Table 1 and associated tables in the Attachment hereto.

Measuring the loss suffered by low-income workers

The appropriate datum point for an analysis of these matters is the position in 2013-14, under the last Labor Budget and at the end of the Rudd-Gillard-Rudd Labor Governments, which ended with the election of the Coalition Government in September 2013. In the 11 years since, CPI increases (June 2013 to June 2024) have been 35.0%. Average wages have risen by a little more. Average Weekly Ordinary Time Earnings for full time adults increased by 35.5% from May 2013 to May 2024. Sources for these are in the Notes to Tables A1 and A3.

Even for those workers who had managed to maintain the real value of their wages, through wage increases of 35.0% over the 11 years, the progressive income tax system was working against them. It was a similar outcome for those whose wages moved in line with the increase in average earnings.

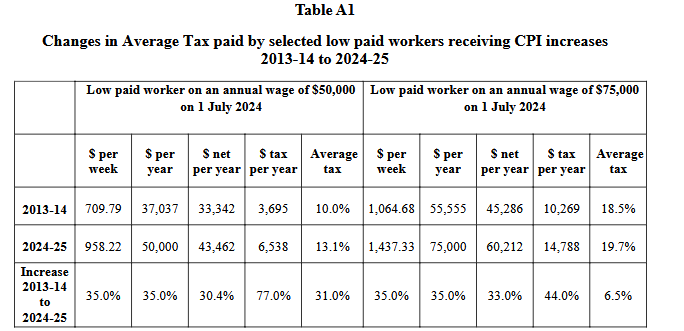

To illustrate: Take the position of the low-income workers now on $50,000 per year who have managed to keep their incomes in line with CPI increases over the 11 years, with gross incomes rising by 35.0% from $37,037. In 2013-14 the income tax payable, averaged across the differing marginal taxation rates, referred to as the “average tax”, or the “tax bite”, was 10.0%, with an annual tax bill of $3,695. The relevant data for this and much of what follows is in Table 1 and, with further detail, in Tables A1 to A6 of the Attachment hereto.

In 2024-25, following the tax cuts introduced in July 2024, the income tax on $50,000 per year is $6,538 and the tax bite is 13.1%, which is 31% more than it was in 2013-14. This is a 77.0% increase in tax paid over the past 11 years. Net income has risen from $33,342 to $43,462, or 30.4%, substantially less than the CPI increase of 35.0% over this period.

This large increase in the tax bite equates to $29.47 per week even after Labor’s July 2024 tax cuts. This is after a tax cut from the previous year’s tax rates of $929 per year, or $17.80 per week. The Labor’s Stage 3 tax cuts reduced the loss from $47.27 to $29.47 per week, a substantial but insufficient amount.

For these workers on $50,000 to have maintained the real value of the after-tax wage in 2013-14 they would now need an income of $52,330 per year, or an extra $44.65 per week pre-tax. To achieve that income, they would need a gross wage increase of 41.3% over a period in which the CPI rose by 35.0%. The data for this and the following worker are in Table A1.

The same kind of calculations can be made for a worker now on $75,000 per year, who has had wage increases in line with CPI increases of 35.0% over the past 11 years. This worker’s net income has increased by only 33.0% while the tax paid has increased by 44.0%. The tax bite has increased from 18.5% to 19.7%, representing a cut in disposable income of $17.50 a week after the Stage 3 tax changes.

The detrimental effects of the tax changes on low-income workers are further demonstrated by the changes in taxation rates for part-time workers who have received CPI-based wage increases over the past 11 years. A worker now on $25,000 is paying income tax of 1.6%, whereas in 2013-14 no tax was payable. For a worker now on $35,000, the income tax has increased from 5.4% to 7.7% of gross because of a tax increase of 90.4%. The gross wage has increased by 35.0% but the tax payable has increased by 90.4%. This represents an after-tax cut in real wages of $15.29 per week on a gross wage of $670.78 per week. The data for these part time workers are in Table A2.

It should be noted that the taxation year 2013-14 is representative of the relative tax burdens on low-income taxpayers in earlier years. Table A7 in the Attachment, which identifies the income taxes paid by workers in two low paid award classifications, shows that the levels of tax paid in 2013-14 were not lower than the averages under the Budgets from 2009-10.

In Table A3 of the Attachment similar calculations are made on the basis that two low-income workers have received a wage increase in line with the 35.5% increase in average weekly adult ordinary time earnings. The worker now on $50,000 per year has had a tax increase from 9.9% to 13.1% of gross income and the worker now on $75,000 per year has moved from 18.4% to 19.7% of gross income.

Middle- and high-income earners

As the Treasurer emphasised, the 2024 changes to the tax system were designed to be weighted in favour of middle-income earners. We can see that in Figure 1, highlighted by the colour coding. The details supporting the following observations are taken from Tables A4 to A6 of the Attachment. The differences in the outcomes for low-income and middle-income taxpayers are stunning.

Let us first compare the position of the middle-income worker now on $100,000 per year, again assuming he or she had received wage increases over the past 11 years in line with CPI changes. In stark contrast to the worker on half that income, this worker now pays 22.8% of that income in tax, only slightly more than the 22.6% in 2013-14.

The tax advantage to middle income taxpayers is much clearer when the income is $150,000 per year, which has income tax at 26.6%. By contrast, in 2013-14 tax paid was 27.7%: Net income has increased by 37.0%, compared to the 35.0% increase in the CPI. This equates to a real net wage increase of $32.81 per week.

So, under Labor’s Stage 3 tax cuts, the worker on $50,000 per year is $29.47 per week worse off while the worker on $150,000 is $32.81 per week better off than they would have been under the relative tax rates applying in 2013-14. How is it fair that the low paid worker has lost $29.47 per week while the worker on three-times the low paid worker’s wage has gained $32.81 per week?

The advantage to middle income workers reduces as taxable incomes rise. At $200,000 per year income tax has been reduced from 30.4% to 30.1%, a marginal improvement. At $250,000 the tax bite has increased from 32.2% to 33.5%, or by 4.0%. This 4.0% increase is a small fraction of the 31.0% increase paid by the worker on $50,000 per year.

Table A6 in the Attachment covers two very high incomes at the upper limits of Figures 1 and 2, again based on a 35.0% increase in the CPI. At $300,000 per year income tax has increased by 3.2% and at $500,000 per year it has increased by 2.0%. These taxpayers are worse off relative to 2013-14, but not as much as the low paid. How is it fair that a low-income taxpayer on $50,000 per year has had a tax increase of 31.0% when a very high-income taxpayer on five-times that income has had a tax increase of only 2%?

Comparing changes across the income groups

This information is illustrated in Figure 1, which shows the changes in Average Tax across income levels, by reference to the 35.0% increase in the CPI over the 11 years. Data underpinning this graph is in Table 1.

Another way of looking at these substantial changes and their impact on the “shape” of our progressive tax system is in Figure 2. This graph plots the average taxes, or tax bites across the current income from $30,000 to $250,000 per year and their levels in 2013-14, again using the CPI index to make the comparison. The data underpinning the graph is in Table 1.

Low paid workers have suffered economic pain

These figures demonstrate that the tax changes over the past 11 years have been very detrimental to low-income workers. Workers earning up to approximately $100,000 per year have had a cut in real net income.

If asked the question whether they are worse off than they were 11 years ago, these workers could truly say that they are.

These outcomes are iniquitous as between low paid workers and those on middle, high and very high incomes. This inequity is likely to be compounded by the ability of many higher income earners to gain wage increases in excess of CPI increases and the inability of many low-income earners to gain even CPI-based increases.

It should also be noted in Figure 2 that the 2024-25 curve in the changes in tax burdens suggest that our income tax rates are insufficiently progressive. Over the income range $30,000 to $130,000, the average tax rate increases from 5.3% to 24.9%, whereas the average tax rate from $130,000 to $230,000 increases from 24.9% to 32.3%. Many would think that a progressive tax system would have a near straight line from the point at which tax becomes payable and the point where the top marginal rate is payable. Figure 2 shows a substantial deviation from that view. Much is made in some public discussion about the need to lower the marginal tax on high income earners to provide work incentives and rewards, but these are considerations that also apply to low- and middle-income workers.

The award system

The minimum wage rates established under industrial awards provide a safety net for many low paid workers. Over the past 11 years minimum award rates have increased at a greater rate than CPI increases, however increasing tax bites have taken most of the benefits of those wage decisions.

This can be illustrated by the lowest rate set for a trade-qualified worker, currently, $53,865 per year. The rate is used in a number of non-trades awards as the key reference point in establishing award relativities. In 2013-14 it was $37,804. This is a 42.5% increase, substantially more than the CPI increase of 35.0%. However, the increase in tax of 97.5% (from $3,967 to $7,833) has reduced the after-tax increase to 36.0%, with the net wage rising from $33,837 to $46,032. Income tax has risen from 10.5% to 14.5%, or 38.1%.

For the cleaner on the lowest minimum wage rate for that classification, the current income is $49,519 per year or $949.00 per week. Over the past 11 years the award wage has increased by 42.8%, but income tax has increased by 98.9%, with the result that it has risen from 9.2% to 12.9% of the award wage, an increase of 40.2%. The net wage increase is 37.1%, which is not much above the CPI increase of 35.0%. This information is drawn from Table A7.

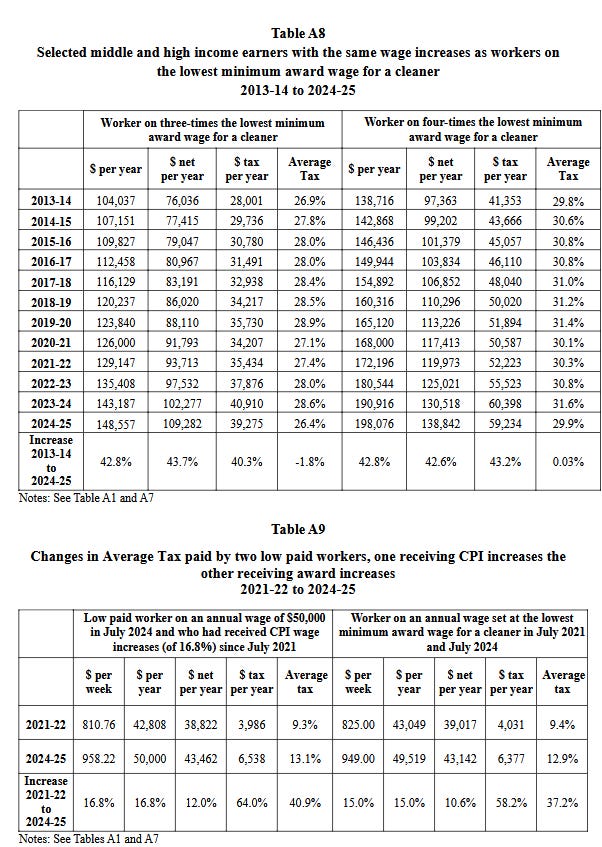

How would higher income earners receiving the same percentage wage increases as these low paid cleaners fare? The outcome for workers on three-times the award rate of the cleaner is quite different. Their gross incomes have risen from $113,412 to $161,595, with the tax payable decreasing a little from 27.9% to 27.5%, in stark contrast to the 40.2% increase for the low paid cleaner. For those on four-times the cleaner’s award rate, now $198,076 per year, the tax payable has barely moved: from 29.8% to 29.9%. This information is drawn from Table A8.

We might expect that incomes in excess of both average wage increases and CPI, as is the case with award increases, will result in some increase in average taxes. However, the fact of the matter is that most of the wage increases granted by the Fair Work Commission (FWC) have been lost through changes to taxation rates that have favoured middle- and high-income earners at the expense of low-income workers.

Table A7 contains some important information about the disposable incomes and living standards as a result of taxation policies over the decade and a half. Average taxes paid by low-income workers award-reliant workers, as illustrated by the two examples given, were quite stable under the Labor Budgets of the Rudd-Gillard-Rudd Governments, but they rose significantly in the following years. By 2021-22 they had returned to their former levels, principally, if not wholly, as a result of the introduction of the Low and Middle Income Tax Offset (LMITO).

But the LMITO was only a short-term measure to end in that year. It was not an “act of generosity” for the low paid because it essentially restored the average taxes of earlier years (2009-10 to 2013-14). Its real purpose was to deliver on the strategy of combining short-term tax cuts for low and lower-middle income taxpayers with long-term tax cuts for high income taxpayers in pursuit of the objective of re-distributing the burden of income tax across the income levels. It was a sugar hit that diverted attention from what was being done to the taxation scales.

Table A7 shows the consequences of the withdrawal of the LMITO. In three years, including after Labor’s July 2024 tax cuts, average tax for the lowest award-paid cleaner has gone from 9.4% to 12.9% and for worker on the lowest trade-qualified rate, average tax has increased 10.5% to 14.5%. In the three years 2021-22 to 2024-25, after-tax wages for the skilled worker increased by 9.6%, yet the CPI increased by 16.8% from June 2021 to June 2024. I will return to a discussion of these three years.

These kinds of changes affecting low-paid workers should be of key concern for trade unions focussed on the low paid. Yet the silence of the trade unions has been deafening.

It is extraordinary that these inequities in the tax system have not stirred opposition within the trade union movement, especially within the Australian Council of Trade Unions, which has the relevant experience and expertise through making annual wage review submissions. They must know how much of the hard-won gains in the award system for the low-paid are being lost though inequitable taxation changes.

Part of the assessments made by the FWC when setting wage rates is the impact of taxation rates on the disposable incomes of award-reliant workers. There is, to some extent, a wage-tax trade-off in setting minimum wages. Increasing income tax rates will generate higher wage increases and/or lower standards of living. Increasing tax rates tend to push up the price of labour and, to the extent that wage and employment levels are connected, will dampen demand for labour. Maintaining or reducing taxation levels for low-income workers will support their living standards while limiting increases in the costs of employment. More attention needs to be given to this aspect.

It might be noted that Average Weekly Ordinary Time Earnings have increased by 35.5% over the 11 years award while the award wages described above have increased by 42.5% and 42.8%. Other award rates have increased by similar amounts. This apparent conundrum suggests that the safety net wages set in the award system are much lower than the actual rates paid across the community and that only a small proportion of workers are paid the applicable award rate.

Is there a way forward?

The increasing tax bites affecting low-income workers have been caused by the failure to adjust the tax scales to reflect inflation (with bracket creep causing increasing average tax rates) and by the freezing or withdrawal of targeted tax offsets available to low-income earners.

Remedying the situation of low-income earners through changes in the relevant marginal tax rates and tax thresholds will not target support for the low paid because these changes would have a knock-on effect that would reduce the tax paid by higher income earners. The remedy should come through an adjustment to the Low Income Tax Offset (LITO), which is a provision targeted at those most in need.

LITO is an income related offset of $700 per year at its maximum. It is phased out at two rates: from $37,501 to $45,000 (where it is $325 per year) it is phased out at the rate of 5% and from $45,001 it is phased out at the rate of 1.5%, with nil being paid at $66,667. LITO does not offset the Medicare levy. Because LITO provides tax offsets, no payment is made to the taxpayer if assessed tax is less than the offset.

I mentioned earlier the short-term tax cuts for low and middle income workers introduced by the Morrison Government, the LMITO, which ended in June 2022. LMITO was also an income-related payment; see column 1 of Table 2, below. The phase out of LMITO was complete at $126,000. At a taxable income of $50,000 it was worth $1,750 per year, or $33.54 per week. The loss of that benefit no doubt was keenly felt by low-income workers and families. At the time (and now) at $50,000 per year the LITO was worth $250, or $4.79 per week.

The figures referred to earlier show that there is a rational basis for the disenchantment of many low-income workers and households with the Albanese Government. In particular, the loss of the LMITO tax offset in June 2022 was very painful for many Australian workers and their families. That loss of an offset once a tax return was lodged was not apparent to many until they submitted their tax returns after June 2023, many months after the May 2022 Federal election. It was, in a sense, a potential poison pill for the victors of that election.

The LMITO payments are important because they provide a guide as to what was, in effect, taken from low-income workers in order to provide tax cuts to middle-income workers. This is not a situation where LMITO should be introduced. Rather, the appropriate response is to increase LITO.

The difficulty is that the massive rebalancing of the tax burden between low and middle incomes and the failure of Labor’s 2024 tax changes to sufficiently remedy them cannot be rectified in one year. The most recent data from the ATO shows that in 2021-22 42.4% of Australian taxpayers had a taxable income of up to $45,000 per year. The number of low-income taxpayers who have suffered from bracket creep exceeds that percentage. Figure 1 shows graphically the size of the rebalancing. It is the dollar value of the area between the two lines up to approximately $100,000.

Table 2, at column 2, provides some quantification of what has been lost following the removal of the LMITO offsets; for example, $675 per year for incomes up to $35,000 and $900 to $1,500 over the range $40,000 to $90,000.

Table 2 provides a proposal for increases in the LITO tax offsets over three years. The first year is 2024-25, which would mean, if enacted, low-income taxpayers could access the increased offset in their tax returns for 2024-25. It proposes an increase in the payment from $700 to $1,000 with a reduction at the rate of 2.0% from $45,001. The increases proposed in Year 1 are modest; for example, at $75,000 the LITO payment would be $400, well short of the earlier LMITO offset of $1,500. Each of Year 2 and Year 3 add to $100 to the maximum payment and reduce at the 2.0% taper rate from $50,001 and $55,001, respectively.

These outcomes are also modest. For example, in Year 3 the offset at $50,000 is $850, compared to the current $250. This represents a benefit of $11.50 per week, substantially less than the loss suffered, where it was shown earlier that the loss for this worker in 2024-25 equated to $29.47 per week even after Labor’s July 2024 tax cuts. At $75,000 in Year 3 the LITO offset it is $600, compared to the current zero. Again, this represents $11.50 per week, compared to the 2024-25 loss of $17.50 per week, as explained earlier.

This three-step proposal will not address the prejudice suffered by the low paid under the Coalition’s 2019 taxation changes, as modified Labor in 2024. They represent a substantial step towards remedying that prejudice.

No doubt some will argue that these steps will be too costly and that they cannot be afforded. A precondition for any debate about that question should be the quantification of what has been lost by the low paid in the framing of the legislation in 2019 and its modification in 2024. Before any opponents argue about the costs of these proposals, they should quantify the cost to the low paid of what has been a major change to our progressive taxation system.

Labor needs to admit the pain and do something about it

Is a change in the fortunes of the low paid a pipedream? Where will the momentum for change come from? It is very doubtful that the Albanese Government will want to say or do anything that exposes the shortcomings of its 2024 tax changes. On the other hand, the current softening of Labor support, especially among its traditional base, should call for the Government to further address the cost-of-living concerns of many taxpayers.

I noted earlier that low paid workers who had received CPI increases in the last 11 years can truly say that they are now worse off than they were 11 years ago. Some naysayers might dismiss these concerns as being outdated. However, we do not have to go that far back.

In 2021-22, the financial year in which the May 2022 Federal election was held, our worker now on $50,000 per year was on a CPI-adjusted wage of $42,808. In the period since, three years of high inflation, the CPI increased by 16.8% (from June 2021 to June 2024), the tax paid on the CPI-adjusted wage has risen from $3,986 to $6,538 per year, or 64.0% (compared to a 16.8% increase in wages), following the withdrawal of the LMITO tax offsets in June 2022 under, it should be remembered, legislation passed by the Morrison Coalition Government in 2019. These workers can truly say that they are worse off than they were in May 2022, even though they have received the July 2024 tax cuts.

Workers who are award-reliant have also had the same kind of cuts in their living standards. For example, in 2021-22 the cleaner on the lowest award rate paid annual tax of $4,031. In 2024-25 he or she pays $6,377, an increase in tax of 58.2% on an award wage that has risen by 15.0%. For this cleaner, weekly tax in 2021-22 was $77.25 and in 2024-25 it is $122.21. The result is that net income has only risen by 10.6% at a time when the inflation has increased by 16.8%. They have good reason to say that their financial circumstances have worsened since the last Federal election. This loss of living standards should be of grave concern to the trade union movement.

The figures supporting the commentary in the previous two paragraphs are in Table A9. Table A10 covers two other workers on CPI-adjusted wages over these years. The worker on $75,000 per year has had a cut in real after-tax income (with tax increasing by 33.4% on a wage up by 16.8%) but the worker on $150,000 per year has had a tax cut of 13.3%.

So, even after the tax cuts of July 2024 low paid workers are worse off than they were when Labor was elected in May 2022. On the other hand, middle- and high-income workers have been advantaged by the taxation changes over the past three years.

Labor’s 2024 tax changes entrenched tax hikes for low-income workers so that middle income workers could have tax cuts. That Labor’s redistribution of tax between low- and middle-income taxpayers was more moderate than those previously enacted under the Morrison Government does not justify them. Most of the earlier redistribution remained. It is no answer to say that the Coalition’s tax plan, which Labor amended in 2024, would have been worse for the low paid. The critical point is that there is a very real basis for the discontent about living standards that appears to be widespread across the community and Labor appears to be taking the political heat for it.

In times like these, a precondition, though not a guarantee, for electoral success by an incumbent government is to acknowledge that it feels the pain of its potential supporters. And it must put forward proposals that address that pain. Labor should send these messages to its base of lower income workers and their families. How can it be re-elected if it does not do so? There are many ways in which Federal funds might be spent, but programmes that do not fill the pockets of voters when they are feeling pain are unlikely to be rewarded.

The Albanese Government should use the May 2025 Budget, or its election platform if it goes to the polls before delivering its Budget, as the first step in addressing the pain inflicted on low-income workers and their families by the inequities caused by the changes to the income tax system over the past decade. It should start by proposing an increase in the tax offset for low-income earners (LITO). A modest but significant way to do this is to adopt the changes set out in Table 2, or something similar to it. Whatever way the Government might do it, the changes should be operative for 2024-25 so that low paid workers can receive the benefits as soon as their 2024-25 tax returns are processed. Beyond that the Government should commit to such further increases that are needed to address the inequities described above.

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

About the author, Brian Lawrence (brianlawrence2000@outlook.com)

Brian Lawrence LL.B. M.Ec. is a retired barrister. He is a former Deputy President of the Industrial Relations Commission of Victoria and a former Chairman of the Police Service Board of Victoria. He was Chairman of the Australian Catholic Council for Employment Relations, an agency of the Australian Catholic Bishops Conference, from 2007 to 2015. From 2003 until 2019 he drafted and presented submissions on behalf of the Catholic Church in the annual wage reviews conducted by the Australian Fair Work Commission and its predecessors. The purpose of those submissions was to support low-income workers and working families.

In June 2019 he wrote on the taxation implications for low-income workers of taxation legislation then being considered by Parliament. The article, The Government’s tax package and Labor’s response: the perspective of a cleaner, was published in Pearls and Irritations. It argued that the Morrison Government’s tax proposals were unfair to low-income workers. Following the Labor Government’s announcement in January 2024 that it would seek to amend the 2019 legislation he wrote two more articles for Pearls and Irritations: Labor’s tax plan fails low paid workers, on 30 January 2024, and One last chance for the low paid to receive tax equity, on 26 February 2024.

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….

ATTACHMENT